Bribing of voters, state use of resources, media bias, harassment of opponents, and questionable results are all part and parcel of Ugandan elections. What can civil society and citizens do to make elections more accountable?

Ahead of the 2006 presidential election in Uganda, we set up UgandaWitness, a website collating reports of human rights abuses. While a number of human rights organisations and media were each reporting on election abuses, there was no single place where you could find a complete record of everything. We compiled reports from NGOs and media relating to election abuses on UgandaWitness, and allowed citizens to add their own reports in real time during the election. Their reports were then shared with NGOs for verification.

In the Kenyan election of 2007, human rights reporting took on new urgency with the outbreak of widespread post-election violence. The Kenyan website Ushahidi, allowed citizens to report abuses by SMS for the first time, and mapped them on a website in real time. Ushahidi was a vital source of information for the media, and civil society. Since then the Ushahidi platform has been Kenya’s most successful tech export: it’s been deployed over 10,000 times across the world.

In 2011 with EU funding, US-based NDI partnered with Ugandan election monitoring organisation DEMGroup to develop a Ugandan version of Ushahidi for the presidential elections.

UgandaWatch2011.org allowed citizens to report human rights abuses by SMS for the first time.

Crowd-sourcing information by SMS can generate a huge amount of information, but it creates a new problem: how do we know whether the reports we are receiving are true or false? This information is very sensitive and needs to be verified quickly to give an accurate picture of what is happening in real time.

The second-level problem is that different reports require different types of verification: a message about a polling station opening 10 minutes late can be verified if it comes from multiple sources; but a message about a shooting requires verification from a trusted and independent witness at the scene.

The answer is to categorise events and determine what should be the procedure for verification of any possible scenario. The result is a complex flowchart that shows the procedure required in each case, and whether the information is published or not; and whether it is published with a “verified” tag.

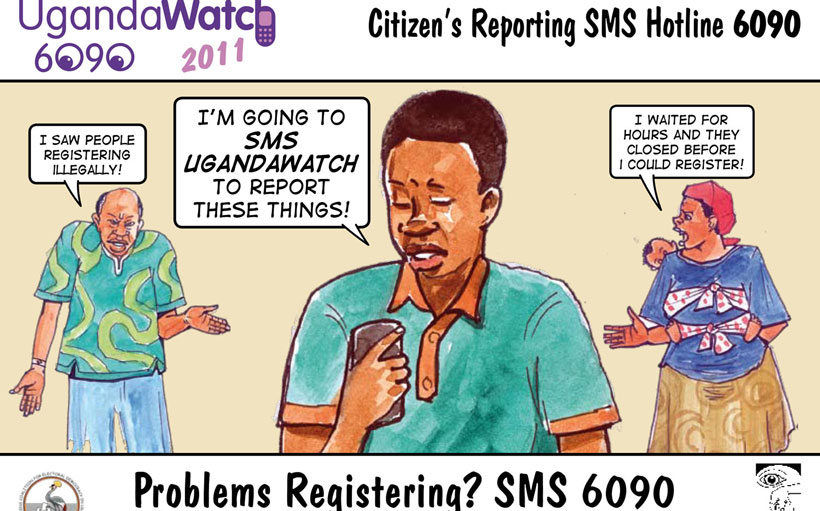

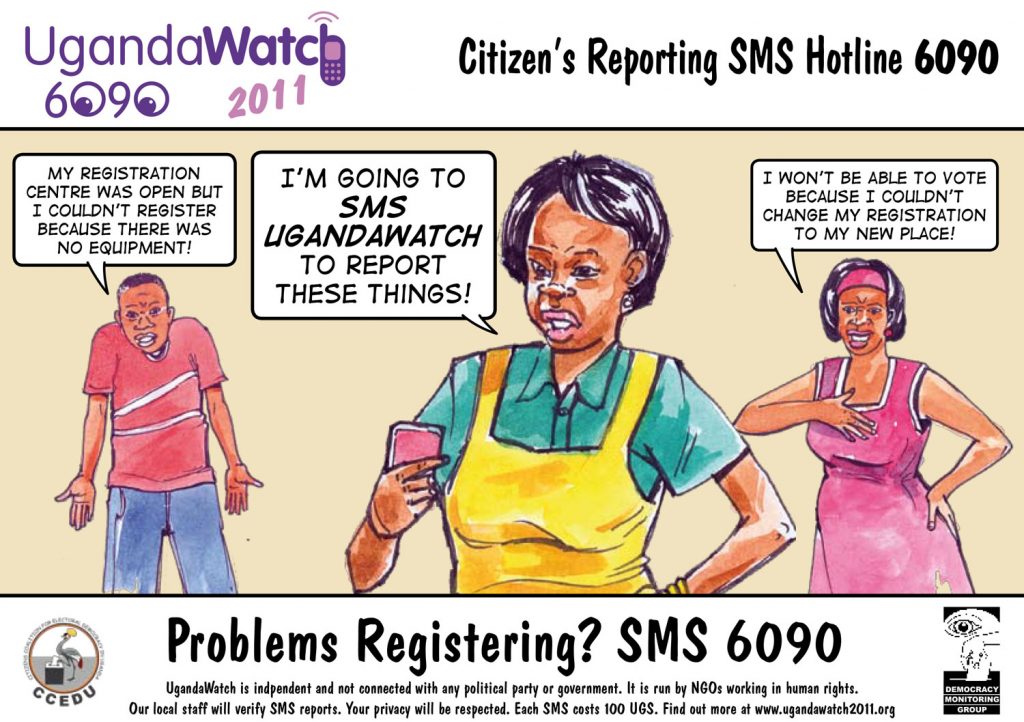

To encourage use of UgandaWatch we used posters, flyers, newspaper ads and radio advert in 6 languages on a dozen radio stations to cover the country. The first poster was designed to introduce users to the purpose of UgandaWatch and how they could use it. A second flyer gave step-by-step instructions on how to SMS the hotline, highlighting confidentiality and explaining the verification process. The illustrations were created by Baingana Andrew.

An example of using a social proof nudge: demonstrating that other people are using a service encourages new users to try it out.